Seva as Sadhana: Sathya Sai Baba’s Vision of Leadership and Transformation

Authors: Brindha B , Dr. Phani Kiran Pothumarthi

- Jun 30, 2025

- 4 views

Abstract

In contemporary leadership discourse, Servant Leadership has emerged as a transformative model that prioritizes humility, stewardship, and service over authority. Sathya Sai Baba’s concept of Seva (selfless service), deeply rooted in Indian spiritual traditions, resonates with the principles of Servant Leadership while extending beyond it as a path to self-realization. Unlike conventional leadership models that focus on governance and organizational ethics, Seva integrates service with practical spirituality, positioning leadership as both a social responsibility and a means of inner transformation. This paper examines Seva through the lens of Servant Leadership while situating it within broader cross-cultural ethical and philosophical paradigms. By bridging spirituality with governance, this study presents Seva as a compelling framework for ethical leadership, social transformation, and comparative philosophical discourse, offering an alternative model of leadership that synthesizes action, devotion, and self-transcendence.

Full Text

1. Introduction

Spirituality has been a significant theme in discussions on servant leadership. Scholars have explored the connection between the two, recognizing servant leadership as a model rooted in ethical values and selfless service. Research by Chekwa and Quasta (2018) offers a structured analysis of these concepts, emphasizing how spiritual awareness shapes leadership qualities. Ulluwishewa (2014) highlights that individuals committed to spiritual growth are characterized by unique guiding values and ethical perspectives, shaping their decisions and leadership style. Additionally, studies have categorized the defining traits of servant leadership, providing a clearer understanding of its essence. Lynch and Friedman (2013) stress the importance of identifying these characteristics, as spiritually evolved leaders naturally cultivate humility, a commitment to serving others, and detachment from personal ambition. These traits align with the broader understanding that true spirituality is not simply an abstract concept, but one that demands the integration of values and an innate feeling of sacredness [1].

Spiritual growth is not a solitary pursuit but an active engagement with the world in service to others. It must be lived and expressed in action and practice. This approach of “Practical spirituality emphasizes experience and realization of self, God, and world—in and through practice but at the same time nurtures humility not to reduce these only to practice” [3]. This journey of realization parallels the path of a servant leader, where true leadership emerges not from authority but from genuine service to others. This concept deeply resonates with the Indian ideal of Seva, or selfless service, which is grounded in the belief that true leadership is an expression of compassion and sacrifice. In this sense, Seva becomes both a spiritual and transformative act, bridging individual realization with collective well-being.

Sathya Sai Baba, one of the most influential spiritual figures of modern India, emphasizes Seva as the highest form of devotion, where selfless service is not merely a duty but an expression of divine consciousness. His teachings align closely with the principles of servant leadership, advocating that true leadership emerges not from authority but from humility, empathy, and concern for others. Similarly, Greenleaf’s (1970) model of servant leadership emphasizes that leadership is not about exercising control but about nurturing and empowering those around us.

By drawing from these perspectives, this paper explores the intersections between Seva and Servant Leadership, examining how selfless service fosters both spiritual fulfillment and ethical leadership. It highlights how Seva, as a form of practical spirituality, transforms leadership into a social responsibility rooted in compassion, humility, and collective well-being.

Servant Leadership:

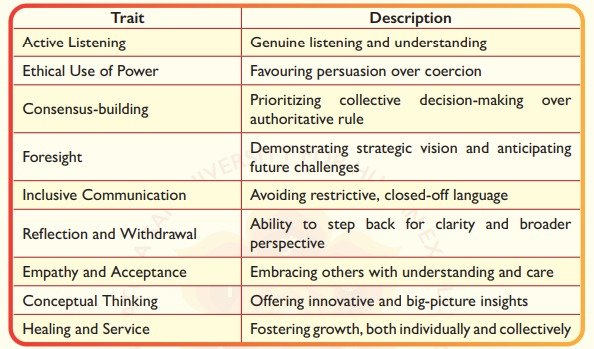

A Brief Overview Robert K. Greenleaf famously stated, “Leadership was bestowed upon a man who was by nature a servant” [6]. His philosophy of servant leadership challenges conventional notions of authority, arguing that true leaders emerge through selfless service rather than positional power. He contends that society needs more servantleaders, individuals who lead by prioritizing the needs of others [6]. The concept of servant leadership was first introduced by Greenleaf (1991), drawing inspiration from Hermann Hesse’s novel Journey to the East. The story follows a group of travelers on a mystical journey, accompanied by Leo, a seemingly humble servant. Their journey unfolds smoothly until Leo suddenly disappears, leading to disorder and the group’s eventual dissolution. Later, when Leo is found and reinstated, the travelers realize that he was, in fact, their leader all along [6]. This revelation highlights Greenleaf’s core message that leadership is not about dominance but service, and the most effective leaders are those who place the well-being of others before themselves. Basing this, in his foundational work, Greenleaf (1991) outlined ten key characteristics that define a servant leader. These characteristics are summarized and presented in Table 1 for clarity and reference.

Greenleaf (1991, p. 4) explains servant leadership as a concept that originates from an innate desire to serve. This desire to serve comes first, followed by a conscious decision to take on leadership. The key distinction lies in the leader’s commitment to prioritizing the highest needs of others. He proposes a fundamental test: “Do those served grow as persons; do they, while being served, become healthier, wiser, freer, more autonomous, more likely themselves to become servants?” In Greenleaf’s perspective, “servant leadership is leadership with two roles of servant and leader fused in one real person” (1991, p. 21).

Greenleaf’s principles of servant leadership were initially applied to business organizations, where they evolved into a model focused on developing and empowering individuals to reach their highest potential (Gandolfi et al., 2017). The underlying belief is that when leaders prioritize the growth of their followers, it creates a ripple effect, enhancing not only individual well-being but also the overall success and performance of the organization (Gandolfi et al., 2017). This model shifts leadership from a hierarchical approach to a participatory and purpose-driven practice.

Similarly, Sathya Sai Baba’s Seva embodies practical spirituality, where leadership is not merely about guiding others but about transforming oneself through selfless service. Unlike conventional leadership models that focus on empowerment within organizational structures, Seva nurtures both the giver and the receiver, fostering inner growth alongside social upliftment. By integrating spirituality with action, Seva transcends institutional frameworks, creating a leadership paradigm rooted in compassion, duty, and the realization of a higher purpose.

Table 1: Summary of Servant Leader characteristics

The Spirit of Seva: Sathya Sai’s Guiding Ethos to Practical Spirituality

In Indian philosophical traditions, the inevitability of action, or karma, is a fundamental principle. The Bhagavad Gita affirms that even the Divine engages in action “for the maintenance of the world” (loka sangraha). It says, na me pārthāsti kartavyaṁ triṣhu lokeṣhu kiñchana nānavāptam avāptavyaṁ varta eva cha karmaṇi (4.18) The meaning of this is, “there is no duty for Me to do in all the three worlds, O Parth, nor do I have anything to gain or attain. Yet, I am engaged in prescribed duties, underscoring the inescapable nature of karma.” According to the doctrine of karma, every thought, word, and deed generates a corresponding consequence. The cycle of birth, life, death, and rebirth is thus governed by karma, which represents the cumulative effects of an individual’s actions. Each positive act inevitably yields a beneficial outcome, while negative actions lead to adverse consequences [8]. Modern thinkers such as Swami Vivekananda, Mahatma Gandhi, Sri Sathya Sai Baba, and other Hindu philosophers interpret “karma not so much as a way of placing blame and more as a doctrine of freedom and empowerment” [8]. If one’s present circumstances are shaped by past actions, then one also possesses the agency to transform them and create a better future. Within this framework, understanding dharma becomes essential. To lead a fulfilling life and minimize suffering, both in the present and in future rebirths, one must discern which actions to perform and which to avoid. So what is Dharma? Baba says, “one should attain unity of thoughts, words, and deeds. This is the true dharma of every human being” [9].

Within this context, Indian philosophy delineates two primary modes of engagement with the world:

The first mode of thought—pravṛitti, or “world affirmation”—is traditionally the value system of the householder, who has a duty to provide support for society through economic activity. In contrast, nivṛtti, or “world renunciation,” is the value system of the ascetic who renounces the lifestyle of the householder to pursue spiritual enlightenment [8].

A key philosophical bridge between these two modes is found in the doctrine of Karma Yoga, from Bhagavad Gita. Karma Yoga, or the path of selfless action, advocates engagement in the world without attachment to personal gain. By performing one’s duties with a spirit of dedication and detachment, an individual can achieve both material and spiritual fulfillment, harmonizing the seemingly opposing values of pravṛtti and nivṛtti.

Sathya Sai Baba reconciles these two aspects by elevating Seva (selfless service) as Sadhana (spiritual practice). In his philosophy, action is not merely a means of worldly engagement but a transformative path to selfpurification and spiritual evolution. Through Seva, individuals transcend self-interest, cultivate universal love and oneness, and attain liberation— “not through renunciation, but through selfless service”, Baba says.

Seva is a small word but is filled with immense spiritual significance... Seva must be viewed as the highest form of sadhana. Serving the poor in villages is the best form of sadhana. In the various forms of worship of the Divine, culminating in Atma-nivedanam (complete surrender to the Divine), Seva comes before Atmanivedananam. God’s grace will come when Seva is done without expectation of reward or recognition. Sometimes Ahamkaram (ego) and Abhimanam (attachment) rear their heads during Seva. These should be eliminated altogether [10].

In this way, Baba synthesizes Karma Yoga and Bhakti (devotion), presenting selfless action as a direct path to self-realization. This aspect of Seva shows how “Practical spirituality is a multi-dimensional movement of transformation and quest for beauty, dignity and dialogues in self, culture and society. Practical spirituality also involves transformation of religion, science, politics, self and society. Practical spirituality seeks to transform religion in the direction of creative practice, everyday life, and struggle for justice and dignity” [11].

According to Sathya Sai Baba, man is inherently a social being. He says, “Society for man is like water for fish; if society rejects him or neglects him, he cannot survive” [9]. Baba here highlights the limitations of individualism and the transformative potential of collective action. He asserts, “What a single individual cannot accomplish, a well-knit group or society can achieve,” [9] emphasizing the power of unity and cooperation. This vision is especially important when it comes to seva, or selfless service. Baba sees seva as a key part of spiritual life— not just to help improve society, but also to go beyond the ego and come closer to one’s true self.

Sathya Sai Baba emphasized on the realization of immanence and transcendence of the Divinity where Selfrealization is the ultimate goal of life, and he reframed the ideal of working for the welfare of the world through the principle of seva (selfless service). He proclaimed, “Manava Seva Madhava Seva” (Service to Man is Service to God) and “Jana Seva Janardhana Seva” (Service to People is Service to God), underscoring that true worship lies in serving humanity with the recognition that the divine resides in all beings.

Here, “Seva is panegyric, that is, it constitutes an expression of the Hindu topography of the self where the prototypical act of worship is the glorification of the divine” [12]. In Baba’s thought, selfless service becomes a sacred offering, elevating both the server and the served through the recognition of divinity in all beings. This makes us understand that seva is not charity but the recognition of divinity in all.

Baba was also in a way a critique of utilitarianism and ritualism. That’s why Prime Minister Narendra Modi aptly acknowledged, “Sathya Sai Baba had done a wonderful job of freeing spirituality from rituals and connecting it to public welfare. His work in the field of education, his work in the field of health, his service towards the poor, down-trodden and deprived, still inspires us [19].” This recognition underscores the transformative impact of seva in shaping a leadership model that transcends personal ambition and focuses on collective wellbeing.

Drawing on Samta P. Pandya’s (2014) analytical framework, we have adapted its structure to Baba’s philosophy, given the conceptual parallels in their approaches to service. Baba’s discourses on seva articulate three distinct yet interrelated dimensions:

Normative – expressed through the dictum Manava Seva Madhava Seva (service to man is service to God), which underscores the ethical imperative of selfless service.

Ideational – rooted in the principle Atmano Mokshartham Jagat Hitaya Cha (for one’s own liberation and the welfare of the world), reflecting the dual objective of spiritual evolution and social responsibility.

Epistemological – encapsulated in a theistic existential framework, which entails:

- The given-ness of worldly existence,

- Suffering as an intrinsic aspect of life,

- The necessity of transcendence,

- The affirmation of divine reality, and

- The role of an institutional mechanism for elevating human consciousness by recognizing the inherent divinity in all beings.

Baba’s understanding of seva is that—service—should become a doctrine of self-realization. The aim of man is not seva, and Baba is clear about it. The aim of man is to perceive God in all. Here Self-realisation and God Realisation are one and the same. Fundamentally it is realising the divine within oneself and in all. Therefore, only serving others out of sympathy can, at the most, make one a philanthropist. One must divinize all their actions; only then is the true meaning of seva realised. This act of divinising work helps one get rid of the false idea of doership. In this process of divinising action, every duty becomes a struggle towards attaining that divinity. To quote his words:

“Every Sai sadhak and sevak has to make the Atma the basis of all activity. He should regard himself as the embodiment of the Divine and realise that the Atma is present in everyone. One should have the feeling that whatever joy or sorrow others experience is equally his. Only then can one render service, conferring joy on others.”

Baba resonates Bhagavad Gita here. The Gita says:

tasmād asaktaḥ satataṁ kāryaṁ karma samāchara

asakto hyācharan karma param āpnoti pūruṣhaḥ

Meaning: “Therefore, giving up attachment, perform actions as a matter of duty, because by working without being attached to the fruits, one attains the Supreme.” (3.19)

What the Bhagavad Gita implied, Baba made explicit. This theistic existential appropriation of Seva positions service as a transformative praxis that bridges temporal existence with spiritual transcendence, integrating ethical action with metaphysical realization.

Such an approach exemplifies Baba’s vision of spirituality as practical and engaged, rather than confined to abstract contemplation. As V.K. Gokak observes, “Baba’s philosophy, in one sense, is a philosophy of pragmatic transcendentalism,” where “iha and para, this world and the next, matter and spirit, are not divorced from each other” [13]. This way Baba highlighted the importance of Vedanta and seva. He viewed Vedanta as a mode of ‘man’ making; an all inclusive contention in three progressive stages of duality, qualified monism and non-dualism.

Baba’s philosophy of Seva extends beyond traditional interpretations by offering a pragmatic model of leadership that integrates spirituality with service. His emphasis on Seva as a leadership ideal aligns with Robert Greenleaf’s concept of Servant Leadership, which envisions ethical and transformative governance. However, while Greenleaf theorized this model, Baba embodied and institutionalized it, making selfless service the foundation of his educational, healthcare, and humanitarian initiatives. By bridging spiritual ideals with practical action, he demonstrated how leadership rooted in service can foster ethical and sustainable models of community welfare.

Seva Through the Framework of Servant Leadership:

Baba asserts, “We require today those who take delight in selfless service, but such men are rarely seen. You who belong to the Sathya Sai Seva Organisation, every one of you, must become a sevak, eager to help those who need it” [14]. Here, Baba establishes the foundational principle of servant leadership—leadership rooted in service rather than authority. Further he continues, “When the sevak (helper) becomes the nayak (leader) the world will prosper.” The transformation from sevak (helper) to nayak (leader), as Baba describes, mirrors Greenleaf’s assertion that true leaders emerge from a deep commitment to serving others. Baba further reinforces this by stating, “Only a kinkara (servant) can grow into a Shankara (Master),” (Baba, 1981, 94) emphasizing that genuine leadership arises not from power but from humility and self-effacement. This trajectory from servitude to mastery encapsulates the essence of servant leadership, wherein “a man who was by nature a servant” [6] dedicates himself to the well-being of others. In this context, Baba’s insightful use of the term “Shankara” is particularly significant, as it not only signifies a leader but also embodies the divine principle. Thus, when Baba admonished, ‘Grow into a Shankara,’ it can be interpreted as a profound call for the individual to transcend the identity and awaken to their inherent divinity

However, Baba cautions against ego, which can distort both spiritual practice and leadership. He warns that “even a trace of it will bring disaster,” underscoring that selfless service must be free from personal pride or ambition[14]. This aligns with Greenleaf’s perspective that servant leadership requires deep self-awareness and the ability to transcend personal ambition in favor of collective growth.

The cultivation of awareness gives one the basis for detachment, the ability to stand aside and see oneself in perspective in the context of one’s own experience, amidst the ever present dangers, threats, and alarms. Then one sees one’s own peculiar assortment of obligations and responsibilities in a way that permits one to sort out the urgent from the important and perhaps deal with the important. Awareness is not a giver of solace — it is just the opposite. It is a disturber and an awakener. (Greenleaf, 1991, 27)

A critical aspect of Baba’s approach to seva was his emphasis on transformation, both personal and societal. He repeatedly stated that service was not merely about addressing material needs but about cultivating a spirit of compassion and ethical responsibility. This resonates with the servant leadership framework articulated by Robert K. Greenleaf, which defines true leadership as a commitment to the growth and well-being of others. It is the mark of one who, as Greenleaf puts it, is concerned and asks, “What can I do about it” [6] thereby placing the needs of others at the heart of leadership.

However, while Greenleaf’s model emerged within the context of corporate and institutional leadership, Baba’s philosophy is rooted in the Indian spiritual tradition, making Seva not just a social duty but a path to self-realization. In a way, Baba’s vision of social transformation carries a Nietzschean undertone—where the pursuit of salvation and the recognition of divinity in all existence parallel Nietzsche’s concept of the Übermensch, representing a higher state of self-transcendence and spiritual evolution.

Empathy and acceptance form the core of Servant Leadership. Greenleaf distinguishes acceptance as the act of receiving what is offered with approbation, satisfaction, or acquiescence. It is not passive but an active embrace of the other’s humanity, including its flaws. He states, “For a family to be a family, no one can ever be rejected,” [6] underscoring that true leadership, much like family, is grounded in accepting imperfection. The empathic leader, Greenleaf argues, must imaginatively project their consciousness into another’s experience, thereby understanding the struggles, vulnerabilities, and needs of others.

Greenleaf goes on to explain that “anybody could lead perfect people — if there were any,” emphasizing that true leadership often involves guiding individuals who are “immature, stumbling, inept, lazy,” yet have the potential for great dedication and heroism when wisely led [6]. Such leadership requires both acceptance of imperfections and a willingness to work with human flaws, fostering growth through understanding rather than correction. This concept of acceptance and empathy finds parallels in Sathya Sai Baba’s philosophy of Seva.

However, while both Greenleaf and Baba emphasize unity and acceptance of others, their underlying frameworks diverge in crucial ways. Baba’s approach to service extends beyond the empathetic understanding of others to an ontological recognition of the divine in every being. Baba teaches that true Seva is not only about accepting others but seeing the divine essence in them, recognizing the interconnectedness of all. As Baba states, “Duty without love is deplorable. Duty with love is desirable. Love without duty is Divine” [15]. Here, Baba underscores that love (Prema) is the primary motivator for service, and it is this love that enables one to see beyond imperfections, recognizing the inherent divinity in all beings.

Unlike Greenleaf’s model, where empathy and acceptance lead to pragmatic action, Baba’s philosophy links these qualities to spiritual transcendence. For Baba, Seva becomes a sacred practice of self-realization, where serving others is both an act of love and a means of spiritual awakening. Baba’s emphasis on service as a divine expression implies a cosmic interconnectedness that transcends the immediate emotional or relational exchange emphasized by Greenleaf.

Additionally, while Greenleaf acknowledges the imperfection of human beings, Baba’s view incorporates a higher, universal perspective—one that sees imperfection as part of the divine play. Baba’s Seva is about transcending human limitations and transforming service into a pathway for spiritual growth. While Greenleaf’s leadership model fosters human growth through acceptance of flaws, Baba’s Seva calls for divine love as the transformative force that elevates both the server and the served. Thus, both leaders champion empathy and acceptance, but Baba extends this to a transcendent love that goes beyond human empathy, positioning Seva as not merely a compassionate act but a spiritual awakening. Greenleaf’s model, while deeply humanistic and relational, focuses on the psychological and emotional needs of the follower, Baba’s concept of service calls for an experiential transcendence of the self and a recognition of the divine in all.

While empathy and acceptance form the foundation of servant leadership, Greenleaf extends this idea into the realm of persuasion over coercion as a means of inspiring ethical action. Rather than enforcing decisions through authority, he argues that true leadership cultivates voluntary transformation: “Persuading people one by one with a gentle non-judgmental argument that a wrong should be righted by individual voluntary action [6].” He further reinforces that “Leadership by persuasion has the virtue of change by convincement rather than coercion [6]” For Greenleaf, the most effective leaders are those who inspire service not through imposition but through personal example and conscious reflection.

Sathya Sai Baba echoes this principle but extends it beyond ethical leadership into the spiritual realm, emphasizing that Seva must be silent, selfless, and free from personal recognition. He warns against reactive service motivated by social validation, stating: “We do not need any publicity or advertisement. Work silently… Prachar (publicity) is not the Achar (practice) of Sai Organization [16]”. Both Greenleaf and Baba reject coercion in service and leadership, advocating instead for persuasion through conviction and self-practice. However, while Greenleaf’s servant-leader seeks to build ethical communities, Baba’s vision of Seva transcends hierarchical structures, framing service as an act of divine love (Prema), where the distinction between giver and receiver dissolves. Thus, where Greenleaf frames service as persuasive and communal, Baba elevates it to a spiritual discipline, where Seva is not just ethical engagement but an instrument of inner and outer transformation.

In a discourse, he said, “I am only a trustee… All these are gifts from devotees” [16]. By calling himself a trustee, not an owner, Baba rejected personal credit and highlighted collective devotion. This mirrors Greenleaf’s idea of leadership as trusteeship, where leaders serve the community rather than seek authority [17]. According to Greenleaf “The mindset of a servant-leader is trusteeship with a view toward internal stakeholders as well as the larger community. [17]”. Because, Servant leadership is a centrifugal force that moves followers from a self-serving towards other-serving orientation, empowering them to be productive and prosocial catalysts who are able to make a positive difference in others’ lives and alter broken structures of the social world within which they operate Greenleaf (1991) laid the philosophical groundwork for servant leadership. While Baba’s leadership, rooted in humility, selflessness, and social responsibility, embodies these principles, making his model of Seva a compelling spiritual pathway, parallel to the servant leadership philosophy.

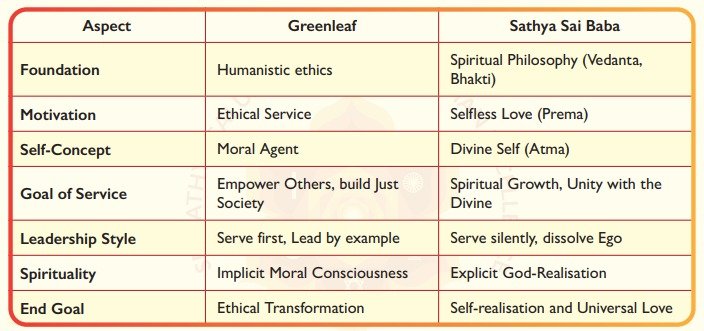

Table 2. A comparative summary of Greenleaf’s servant leadership and Sathya Sai Baba’s concept of Seva, focusing on their foundational principles and intended outcomes.

Conclusion:

V.S. Barulin (1999) identifies the main facets of spirituality: its universality, ideality, and the subjective world. These elements encompass a variety of spiritual dimensions, including rational, emotional-affective, epistemological-cognitive, value-oriented, and worldview-related aspects. Spirituality embodies scientific concepts, moral values, religious beliefs, aesthetic categories, and common knowledge. It is believed that these factors are interconnected and collectively shape the spirituality of both individuals and society [2].

Barulin’s identification of spirituality as encompassing rational, emotional, epistemological, and value-oriented dimensions suggests that spirituality is not confined to personal belief or religious practice but is deeply interwoven with a shared life of values and connection.

Leadership, as a facet of spirituality, manifests in the ability to guide and uplift others through ethical action, wisdom, and selflessness. Swami Vivekananda’s assertion that “the highest idea of morality and unselfishness goes hand in hand with the highest idea of metaphysical conception” [3] underlines this integration. True leadership is not just about governance or authority; it is about embodying and enacting spiritual ideals in ways that transform individuals and society.

Spiritual leadership, as exemplified by Sathya Sai Baba, aligns closely with the principles of practical spirituality and servant leadership. His approach was not about asserting religious or institutional authority but about transforming everyday life into a spiritual practice. This transformation, as A.K.Giri states, is rooted in “sacred non-sovereignty, which embodies a new ethics, ethics and politics of servanthood in place of the politics of mastery” [11]. Baba’s leadership was not about control but about service—an ethical and spiritual commitment to uplifting humanity through selfless action.

Baba’s leadership rejected the divide between the sacred and the secular, demonstrating that spirituality must manifest in tangible service to society. His philosophy did not seek mastery over others but cultivated a space where individuals could awaken to their highest potential through love, education, and selfless service.

This struggle for transformation, as A.K.Giri (2010) notes, encompasses “food and freedom, universal selfrealization, transformation of existing institutions, and creation of new institutions” [11]. Baba’s service initiatives—providing free healthcare, education, and water supply projects— directly embodied these goals. His leadership was not about wielding authority but about fostering dignity, ethical living, and the common good, aligning with the idea of sacred non-sovereignty.

In an era where leadership crises and ethical failures are increasingly prevalent, Baba’s Seva-based model provides a compelling alternative, demonstrating that true leadership is not about power but about purposeful service and commitment. By integrating spirituality with governance, his vision challenges conventional paradigms, urging leaders to see service as both a duty and a path to personal and societal transformation. This reframing of leadership as a spiritual discipline not only enhances ethical governance but also fosters a world where leaders lead not to rule, but to serve.

Author Contributions: Investigation, review, and editing— P.K.P.; Conceptualization, writing, original draft preparation— B.B. All authors have reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript for publication.

Funding: This research did not receive any external funding. Informed Consent Statement: Not applicable

Data Availability Statement: Not applicable

Acknowledgments: The authors express their appreciation and gratitude for the support provided by Sri Sathya Sai University for Human Excellence, Kalaburgi in facilitating this research.

Conflicts of Interest: No conflict of interest

References:

1. N. A. C. Samarasinghe, U. A. Kumara, M. S. S. Perera and R. Ulluwishewa, “Spirituality and Servant Leadership:

A Personal Reflection of a Corporate Leader.”,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Servant Leadership, Palgrave

Macmillan, 2023, p. 1105–1132.

2. G. A. Shadinova, G. B. Dairabayeva and A. Z. Maldybek, Recognizing Spiritual Space: Discovering the Inner

Dimensions of Human Life. Philosophy Hikmet, vol. 1, no. 1, 2024.

3. A. K. Giri, Ed., Practical Spirituality and Human Development: Transformations in Religions and Societies,

Springer Nature Singapore, 2018.

4. S. Radhakrishnan, Ed., The Principal Upaniṣads, HarperCollins Publishers, 1994.

5. S. S. B. Sathya Sai Speaks: Discourses of Bhagavan Sri Sathya Sai Baba, Sri Sathya Sai Books & Publications

Trust, 1998.

6. R. K. Greenleaf, Servant Leadership: A Journey Into the Nature of Legitimate Power and Greatness, Paulist

Press, 1991.

7. S. Dhiman, “Gandhi An Exemplary Servant Leader Par Excellence,” in Palgrave Handbook of Servant

Leadership, Palgrave Macmillan, 2023, pp. 1-22.

8. J. D. Long, “Work Is Worship” Swami Vivekananda’s Philosophy of Seva and Its Contribution to the

Gandhian Ethos,” in Post-Christian Interreligious Liberation Theology, Springer International Publishing,

2019, pp. 81-98.

9. S. S. S. M. C. Sathya and Dharma are Natural are Natural Attributes of Man, vol. 7, Sri Sathya Sai Media

Centre, 2022.

10. S. S. Baba, Sathya Sai Speaks: Discourses of Bhagavan Sri Sathya Sai Baba, vol. 18, Sri Sathya Sai Books and

Publ., 1997.

11. A. K. Giri, “The Calling of Practical Spirituality,” 3D... IBA Journal of Management & Leadership, vol. 1, no.

2, pp. 7-17, 2010.

12. S. P. Pandya, “Seva in the Ramakrishna Mission Movement in India: Its Historical Origins and Contemporary

Face,” History and Sociology of South Asia, vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 89-113, 2014.

13. V. K. Gokak, Bhagavan Sri Sathya Sai Baba: He Man and, Abhinav Publications, 2003.

14. S. S. S. Baba, Sathya Sai Speaks, vol. 15, Sri Sathya Sai Books, 1981.

15. S. S. Baba, Summer Showers in Brindavan, 1979: Discourses of Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba Delivered

During the Summer Course Held at Brindavan on Indian Culture and Spirituality, Sri Sathya Sai, 1979.

16. S. S. Baba, Grama Seva is Rama Seva: Global Spiritual Renaissance Through Service to Villages, Convener,

Sri Sathya Sai Books and Publications Trust, 2000.

17. P. Mathew, “Neuroscience and Servant Leadership: Underpinnings and Implications for Practice,” in The

Palgrave Handbook of Servant Leadership, Palgrave Macmillan, 2023, pp. 1573-1596.

18. S. S. Baba, “Seva is the highest Sadhana,” [Online]. Available: https://saispeaks.sathyasai.org/discourse/sevahighest-sadhana. [Accessed 14 February 2025].

19. Modi, Narendra. 2022. pmindia.gov.in. https://www.pmindia.gov.in/en/news_updates/pms-remarks-atinauguration-of-shri-satya-sai-sanjeevani-childrens-heart-hospital-in-fiji/?comment=disable.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of SSSUHE and/or the editor(s). SSSUHE and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions, or products referred to in the content.